The Why and How for Balancing Amino Acids

Feeding excess protein is expensive. If we aren't balancing amino acids with the necessary energy for growth, we risk wasting protein in the diet.

Looking at crude protein (CP) content alone is an outdated way to approach calf nutrition. How we feed calves today is becoming more in line with how we feed our cows— more nutrient based, and less ingredient based. This article focuses on nutrient balancing for amino acids and energy, and the recurring relationship between the two. By fine-tuning the amino acid to energy ratios, you can expect a more efficient cost per pound of gain and more efficient nutrient use. Formulating feeds this way is not new and has been used extensively in the monogastric and mature cow space for decades.

Why: A Research Proven Concept for Feed Efficiency and Nutrient Management

The newborn calf is the most efficient animal on the farm with respect to utilizing protein, but the right building blocks need to be provided. If we are just providing a high protein diet, not ensuring the amino acids are balanced AND not providing enough energy for utilizing the high amount of protein, we risk much of the protein being wasted. The concept of ideal proteins (a protein with an amino acid profile that meets the animal's requirement exactly so that all amino acids are equally limiting for performance) and amino acid balancing using synthetic amino acids have allowed the poultry and swine industries to improve feed efficiency, waste less nutrients, and lessen feed costs for decades. A calf is much closer in digestive physiology to a pig early in life due to their lack of a functional rumen, which warrants some comparison between the two species.

However, there is a gap in our understanding of microbial protein production when going from a non-functional to a functional ruminant. Some researchers have reported rumen microbial populations in growing heifers do not resemble mature cow populations until at least 6 months old. Moreover, research from the University of New Hampshire showed the proportion of microbial protein to total protein present in the abomasum, or true stomach, increased from 2 to 11 weeks (about 2 and a half months) old. Studies have also shown starter digestibility increases with age and is influenced by both the milk feeding program and the starter formula.

Many dairy farmers understand the pitfalls of overfeeding protein to their cows, and the production loss that can occur when a lactating cow must divert energy from milk production to excrete excess nitrogen. What they might not know is that it could be more taxing on the young calf to excrete excess nitrogen because they do not have a fully developed rumen to help recycle it.

How: Balancing the Cycle-Relationship Between Energy and Amino Acids

First let us define energy balancing—simply, energy balancing is matching the amount of energy consumed with the amount of energy expended. “Energy consumed” can be calculated by accounting for the nutrients in your calf’s diet that are included as energy sources. The “energy expended” relates to energy use by the calf. The two energy requirements we are trying to meet when feeding calves are: Maintenance energy requirements – Calves will first expend energy for metabolic processes like breathing, immune system function, digestion, and regulating body temperature (see Table 1). Growth – After maintenance energy requirements are met, calves will utilize any available energy to metabolize amino acids for tissue growth and repair.

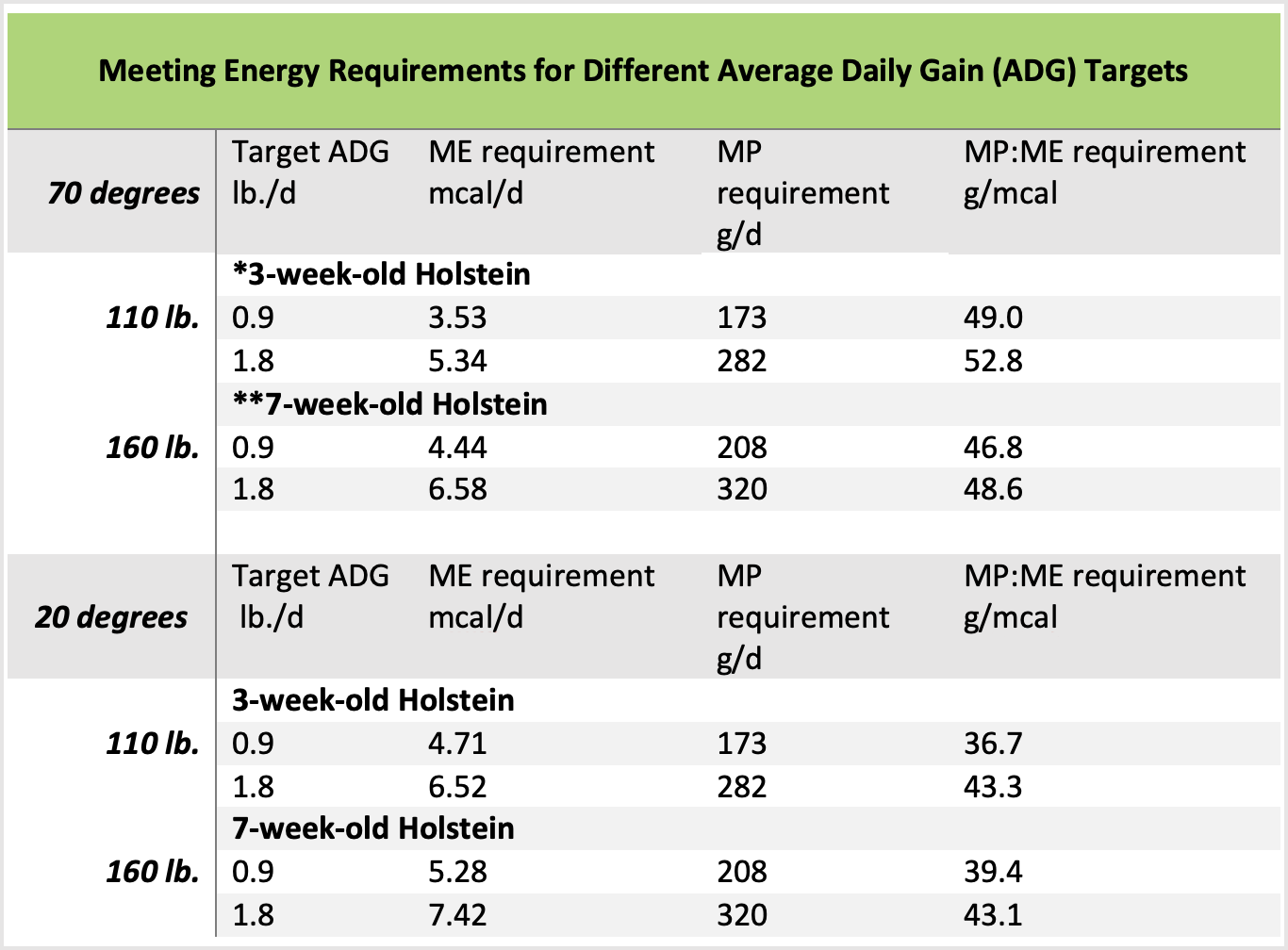

TABLE 1

This table illustrates that the proportion of metabolizable protein intake (MP) required for every unit of metabolizable energy intake (ME) decreases with age, meaning energy becomes more limiting to growth as calves consume more starter as a proportion of their total dry matter intake. Thermal comfort (cold stress) will increase energy required without changing protein intake requirements, meaning energy becomes more limiting to growth regardless of age.

Balancing energy with amino acid intake is a cycle. Energy requirements will drive feed intake because a calf will consume the calories required for a given energy demand, be it dissipating heat in summer or growing 2 pounds per day in the winter. Subsequently, as energy requirements go up, feed intake goes up, and total amino acid intake increases. As noted above, those amino acids are used for tissue growth and repair. A calf will grow if the energy supply is available and driven towards growth.

In typical calf feeding programs, energy and amino acid intake from milk is constant as calves receive a fixed amount of solids per day (unless on an unrestricted program or on an automatic feeder). Once calves are eating starter, additional energy and amino acids are provided through starter consumption. As starter intake goes up, a calf’s total energy supply increases along with body weight. As the calf gets bigger, energy requirements go up and the cycle continues.

The key point to remember is that the actual amino acid intake needed to satisfy amino acid requirements is highly dependent on the energy content in the diet

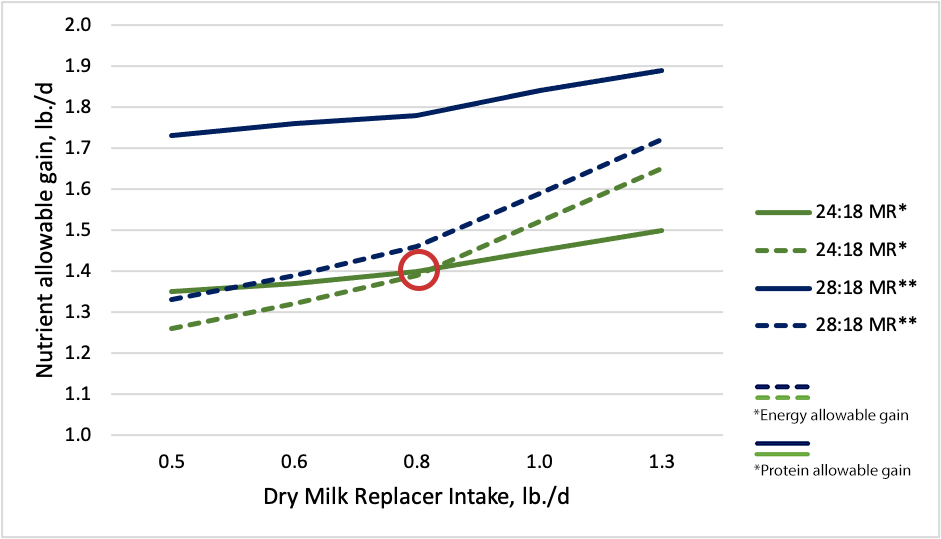

This cycle is important because the industry has pushed for feeding higher crude protein diets to encourage greater growth rates before weaning. However, this can lead to mis-matching protein and energy intakes and result in wasted nutrients (see Graph 1). Bringing everything back down into balance is where we can anticipate a more efficient cost per pound of gain and improved nutrient efficiency.

Graph 1

This is a simulation comparing predicted growth between a moderate protein and fat milk replacer fed with a 18% CP calf starter and a higher protein milk replacer fed with a 22% CP calf starter as they start the weaning transition period (assuming 50% decrease in milk replacer intake to initiate weaning). Notice for the higher protein diet, energy is always limiting growth as we start the weaning transition as indicated by the gap between energy-allowable and protein-allowable gain even at a high milk replacer allowance.

Putting into Practice on Your Dairy

Implementing a feeding program based on the previously discussed concepts all depends on your farm’s goals. Every operation has a different business strategy which determines specific goals, like calf growth benchmarks. So, a calf feeding program that works best for your operation is one that we should be striving for. To do that, we must start thinking about the actual nutrient intakes—not just crude protein on a feed tag—required for your specific calf program.

A place to start is tailoring your starter feed to your milk feeding program. Calves are fed more milk compared to 20 years ago and our calf nutrition programs should evolve to complement increased milk allowances. Feeding more milk increases the maintenance energy “floor,” which in turn means that we need to step up the energy intake in the other half of the feeding program – the starter diet. Ask your nutritionist about the amino acid and energy content in calf feeding program to discover if it meets and optimizes your farm’s goals.